The Art and Science of Natural Dyes Principles Experiments and Results

It is heady to encounter such a passion for indigo these days, and specially the active exploration that is happening. With this also comes with a deeper understanding of indigo dyeing and procedure.

Vats reduced with chemicals such as sodium hydrosulfite or thiourea dioxide used to be the norm when I first learned indigo dyeing in the 1970'southward. But now, many dyers have abandoned those chemical reduction vats and are returning to more benign processes. They are now making quick-reduction vats that are reduced with sugar, fruit, plants, or fe – cheers to the teaching of Michel Garcia. Some are growing their own indigo to explore fresh foliage dyeing and pigment extraction. Others are making sukumo – a long process of composting persicaria tinctoria leaves – Give thanks you lot Debbie Ketchum Jirik for offering an online grade this past fall. Recently, Stoney Creek Colors has introduced a natural, pre-reduced indigo. And more dyers than ever are now exploring vats that are reduced by fermentation.

Fermentation is the process that has captured my interest in recent years. The long-term committment seems to fit my own "stay at dwelling house" life right at present. The lower pH is suitable for all fibers. About of all, information technology's been an interesting risk. Something that once felt out-of-accomplish has now become my preferred process.

The fermentation vat utilizes plant textile to initiate and maintain an alkaline fermenting process, which causes the indigo to become soluble. During fermentation, plant textile is cleaved down, creating bacteria. Lactic acid is produced, making information technology necessary to monitor the pH on a regular ground.

Madder root is a mutual plant textile used in a fermentation vat. In that location is a long history of its use in indigo vats. Information technology is normally combined with wheat bran, which ferments readily. There are many recipes in old manuals for this Madder Vat.

From The Dyer's Companion past Elijah Bemis (originally published in 1815, Dover Edition, 1973)

for a vat of 12 barrels (non sure what a "barrel" is)

- 8 lbs potash

- 5 lbs madder

- four quarts wheat bran

- 5 lbs indigo

When I outset leaned of these vats made with madder, I struggled with the idea of using perfectly good madder root to reduce an indigo vat. But I accept at present come to sympathise that these vats were most likely fabricated with "spent" or "used" madder. I remember Michel Garcia talking nearly how the "used" madder from professional dye studios in the past was sold to the indigo dyers after it had been used to produce cherry-red dye. Indigo dyers have no demand for madder's red colorants and thus nothing was wasted.

So, I am dismayed each fourth dimension I hear from someone who has made a fermented indigo vat using "new madder root". "Spent" or "used" madder is as as effective every bit a fermentation booster as fresh or "unused" madder.

Most of the madder I apply in the studio is in the form of finely ground roots, though chopped roots would piece of work as well. When my madder dyebath is finished, I strain the ground roots and dry them for later use in an indigo vat. It's that simple! And nothing is wasted.

Establish materials, other than madder, can be used in the fermentation vats. I frequently use dried indigofera leaves, equally well as woad balls and take even begun a "hybrid " vat using sukumo with indigo pigment. My most recent experiments have used both Dock root and Rhubarb root successfully. Madder, Dock and Rhubarb are all roots, all anthraquinones…..

Why would a white plastic button plough purple from an indigo dyebath?

Indirubin is i the well-nigh curious components of indigo. It is sometimes referred to every bit the "red" of indigo. Indirubin merely occurs in natural indigo and yous will not detect it in a synthetically produced pigment. Indirubin is valued for its medicinal applications.

Some dyers take been successful at manipulating the extraction and pH of indigo in order to reveal the mysterious imperial/red color of indirubin on a material. I have no real experience with this process.

At one point I did acquire how to analyze an indigo pigment in order to determine the presence of indirubin. If indirubin is present, it is an indicator that the pigment is made from plants and non synthetically produced. Natural indigo has varying amounts of indirubin. The process of analyzing uses solvents and chemicals so information technology is non something that I want to do on a regular basis.

I purchase all of my indigo pigment from Stony Creek Colors, as I know that their indigo comes from plants (and, consequently, contains plenty of indirubin).

Now that I maintain several large "active" indigo vats, I will occasionally dye a ready fabricated garment. A white linen blouse is not a good choice for wearing dress in the dye studio, only one that has been dyed a rich indigo blue is perfect.

After dyeing, just before the final rinse, I e'er boil an indigo dyed fabric in order to remove any unattached dye. Cellulose is boiled vigorously with a small amount of neutral detergent for about x minutes. Wool and silk are brought to a well-nigh simmer and held at that temperature for the same amount of time.

In one case I started using indigo from Stony Creek I noticed that the water from the final boil was always tinted a purple hue. I assumed this was the indirubin that was being rinsed from the fabric. Interestingly, I observed that the purple colour in the boil h2o is temporary, and volition disappear as the bath cools.

Recently, I dyed some linen shirts that had plastic buttons. The buttons stayed white until the final boil. When the garment was removed from the boil bathroom, they had go purple. I have now learned that indirubin is less easily reduced and the undissolved indirubin will stain plastics and other petroleum derived materials. Some of the polyester threads used to sew the shirts are also tinted purple.

Summer Arrowood, the chemist at Stony Creek Colors, tells me that all the plastic vessels in her lab are dyed royal from the indirubin!

Volition these buttons remain purple after multiple washings? I don't know. There is always more to observe and learn from the natural dye process.

Natural dye has never been a quick style to color my textiles. Starting time in that location is the mordanting, then the extraction of constitute/insect material – not to mention growing, gathering, or drying the plants. Did I mention collecting seed? And what about the weaving, where I actually make textile from threads?

These last xviii months at home have been a chance to dive in deeper (and slower) with some processes. Simply before COVID came to our doors, a friend gave me a small jar of sourdough starter. So yes, I am one of those who has fabricated sourdough breadstuff every week for the last year and a one-half. What a gift – both sour dough starter and the time to employ it!

-

Bread made from local, "slow processed" flour from Carolina Footing

It was my fermented indigo vats that gave me the backbone to take on sourdough breadstuff making. I thought that if I could keep indigo vats alive for a number of months, then I could certainly proceed a sourdough starter going likewise. That has proved to be truthful.

The get-go fermentation vat was started in July of 2019. It was a relatively pocket-sized vat (20 liters) but I used it a corking deal. A year later information technology was used it to "seed" a larger 50 liter vat. The success of this first experiment gave me the confidence to start 2 more fifty liter vats in 2020. All are even so going strong. Over the terminal two years I accept fabricated many boosted one-liter vats in order to exam reduction fabric, alkalinity etc. That first large vat that I created in 2019, subsequently existence used heavily for over two years, is finally giving me lighter blues.

Now I am in the midst of another slow procedure – sukumo. Debbie Ketchum Jirik of Circumvolve of Life Studios very generously took a group of zoom course participants through the entire process of small batch composting of indigo leaves based on the teaching and book of Awonoyoh. Every 3-4 days we logged in, watched the sukumo being lifted from its container and stirred past hand. Does it need water? Does it need heat? What does it aroma similar? Conversations were focused and interesting. Several course participants were likewise in the procedure of making their own sukumo forth with Debbie. I am non so fortunate. I have to gather more seed, grow more plants, and dry more than leaves before I will have plenty institute fabric to do my own composting.

This feel has given me a far greater appreciation of sukumo. I was recently gifted a significant amount of sukumo and had planned on making my ain large sukumo vat. Now, understanding more of what sukumo is, I am experimenting with using smaller amounts of sukumo in combination with my fermented indigo pigment vats. When I told my Japanese colleague, Hisako Sumi, near this, she indicated that Japanese industrial production has used this arroyo since early in the early 20th century. There is even proper name for this hybrid: "warigate". Yoshiko Wada translated this for me as "WARI GATE" / "dissever vatting" and it was more often than not done using synthetic indigo.

I have made many minor test vats, using varying amounts of sukumo, in improver to indigo pigment and other materials to boost fermentation. These test vats were ultimatley used to 'seed" a larger vat. I now have my own 50 liter hybrid vat that combines sukumo with Stony Creek indigo pigment.

-

Test vat -

Building the 50 liter"hybrid" vat

-

Successive dips in 50 liter "hybrid" vat

My latest "slow process" is vermiculture. I recently spent an afternoon with friends, sorting worms from castings and beginning my own worm "farm". This is another of those long term, dull processes that bring me closer to the earth, and makes me appreciate the minor miracles of watching things grow. And I know that this compost will feed my indigo plants.

Only not everything must be slow….

Stony Creek Colors has just released information almost their newest product: IndiGold. It is a pre-reduced liquid indigo, grown in Tennessee and designed to be used in combination with fructose and lime (calcium hydroxide). I accept dyed with the before bachelor pre-reduced indigo merely I was never certain exactly what information technology was and didn't want to use the reduction chemicals that were recommended. I stopped using that product a long time ago when Michel Garcia introduced united states of america to the "quick reduction" vats made with saccharide and lime. Just in that location are some occasions, particularly when teaching a ane-day workshop, that information technology is incommunicable to make a vat and dye with information technology on the same day.

Stony Creek sent me a kit for exam dyeing and I was amazed at how quickly the vat was reduced and dyeing to full strength. It took only minutes – non hours. Stony Creek Colors told me that they"skip the chemicals" and use an electric hydrogenation procedure plus an alkaline to reduce the indigo. There are no chemical reduction agents! I used the vat all twenty-four hour period long and it was nevertheless in reduction the adjacent day.

This will not replace my dull, fermentation vats just it will make "quick" dyeing possible when needed.

Once once again, Stony Creek is changing how we remember nearly indigo and its product. They are currently posting information through a Kickstarter Campaign to back up this new venture.

-

IndiGold vat x minutes after mixing -

IndiGold examination strip compared to vat made with comparable amount of Stony Creek pigment. Dyeing was washed immediately afterwards mixing the vats.

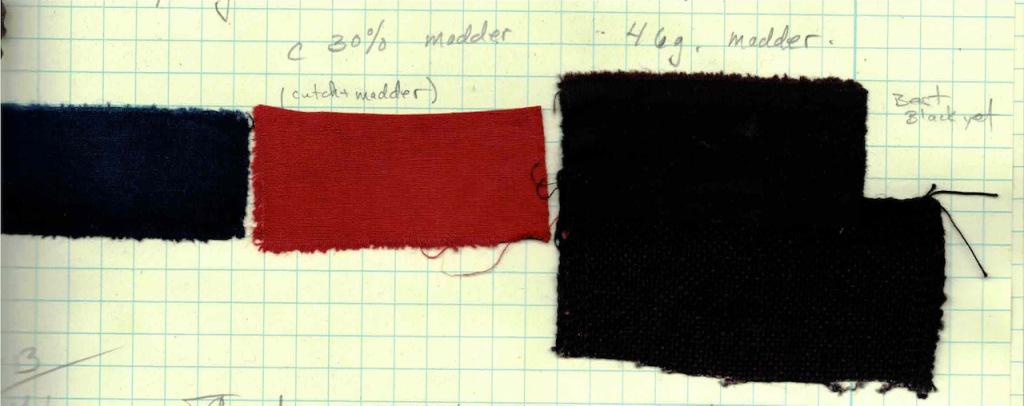

I recently took on a small weaving commission that required the apply of black wool yarn. For a brief moment I contemplated purchasing the wool in the required color and then decided that I could dye it. I was surprised at how like shooting fish in a barrel it was to achieve a rich, deep black colour on the wool using just indigo and madder.

It inspired me to continue my current series of color studies, woven in cotton and linen, with an in-depth exploration of blackness dyes.

Initially, I wanted to accomplish all the black hues without the use of an iron mordant. My years of mixing hues with primary colors gave me the confidence to believe that I could mix a skilful black for cellulose using 3 primary colors: blueish, cherry-red, and yellowish. The fundamental was going to be finding the correct proportions.

The first step was to build up a deep layer of indigo blue (usually 8-x dips in the vat) followed by a mordant, and finally red and yellow dyes. That crimson could be madder or cochineal but I chose to use but madder, since that is what I am growing in the garden. My preferred yellow is weld. Each different combination results in a subtle variation. Some "blacks" are more than purple, while others are a flake more green, or chocolate-brown. I began using black walnut and cutch every bit a substitute for the madder and weld and sometimes added madder or weld to those. Each is a singled-out hue, and definitely in the "black" family. I am confident of the lightfastness of these hues considering of the chief dyes that have been used.

These multiple shades of black, put me in listen of the paintings in The Rothko Chapel in Houston, which is the site of a series of large large "black" canvases by the artist, Mark Rothko. These black canvases are painted with layers of red, alizarin, and black.

But no exploration of black would be complete without some experiments using tannin and iron. Instead of building upwards layers of primary colors, I soaked the textile in a gall nut tannin bathroom, followed by a short immersion in an iron bath. I wanted to use as piddling iron as possible, simply yet accomplish a very night shade. I decided that three% weight of cobweb would be the limit of the corporeality of atomic number 26 I would use.

Most often, I employ ferrous acetate instead of ferrous sulfate considering it is less damaging to the fiber. Cellulose fibers are are somewhat tolerant of ferrous sulfate and so I did experiments with both. That is where I was most surprised! Without exception, the ferrous acetate resulted in deeper colors than the same corporeality of ferrous sulfate.

Why? I wasn't certain. Then I consulted my colleague, Joy Boutrup, who ever knows these things.

"I think the reason for the grayness instead of blackness with atomic number 26 sulfate is due to the college acidity of the sulfate. The acetate is much less acidic. The tannin complex cannot form to the same caste equally with acetate."

The pH of my ferrous sulfate solution was 4. The ferrous acetate was pH 6. (My tap h2o is from a well and is a slightly acidic pH6.)

The grey and blacks achieved with the tannin and iron are quite one-dimensional compared with those that issue from a mix of colors and non well-nigh as interesting, Yet they are likely a more than economic approach to achieving black; the multiple indigo dips, mordanting, and over-dyeing takes considerably more time and materials than an immersion in a tannin and an iron bath.

Ever observing always learning, here in the mountains of Due north Carolina…

Over the years I have congenital, used, and discarded many indigo vats. Sometimes I have kept them going for a very long time. I have finally declared the 5 year old, 100 liter henna vat "done". I accept added indigo pigment, lime and additional henna to information technology many times and although it is notwithstanding dyeing well, the space bachelor for that dyeing (in a higher place the "sludge" at the bottom) has gotten very, very small.

Every bit many of you know, I have spent this last twelvemonth at dwelling house getting to actually know my fermented indigo vats. I accept followed a rather strict protocol. Each vat began with a certain amount of indigo pigment, a source of alkalinity (soda ash or wood ash lye) and various found based materials to brainstorm and sustain the fermentation (wheat bran, madder root, dried indigofera leaves, etc.). Only small amounts of lime and bran have been added over the last yr to sustain pH and fermentation. At no fourth dimension have I added additional indigo.

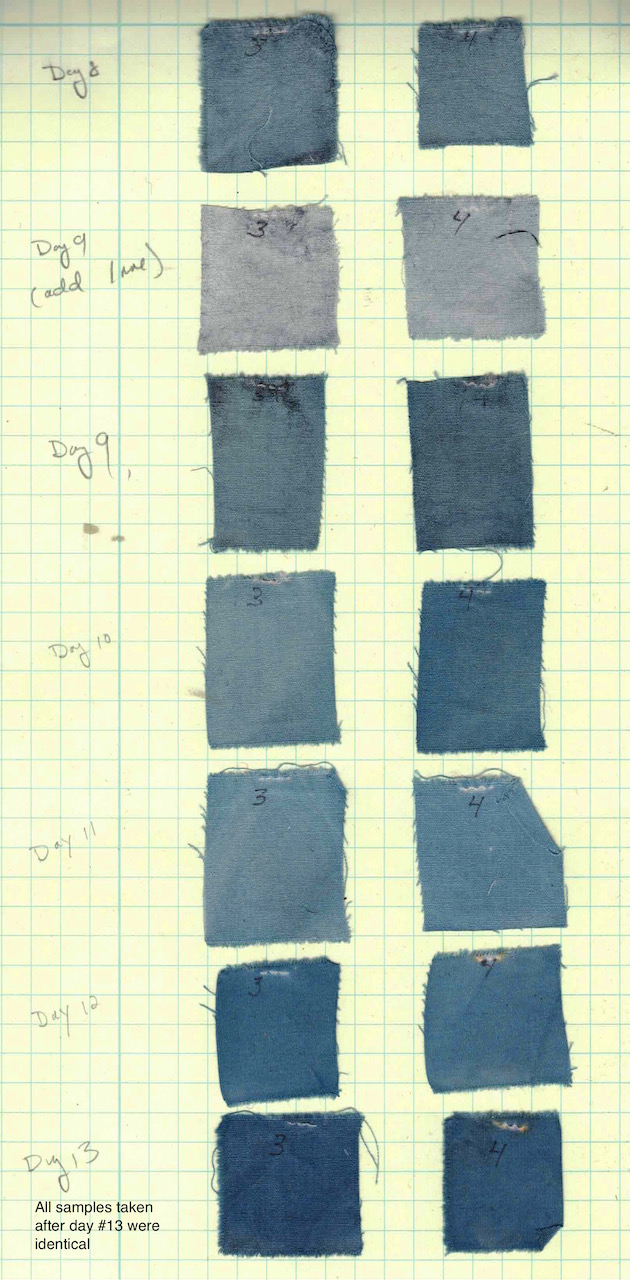

Final May I was trying to attain a broad range of blue shades from the very palest to very darkest. I was a bit dismayed to find that all of my vats were dyeing as well dark to give me the pale shades I desired at the time. I knew (in theory) that if used the vats enough, the indigo content of the vats would decrease but had no idea how long that would accept, or how much dyeing I would need to do. No thing how much I dyed, it didn't seem to happen.…

Now, a yr later on the vats were get-go made, I can see progress.

Indigo on cotton cloth, same vat: 1-24 10-minute dips. February, 2021

Some observations:

This is a long procedure….

Two dips in May, 2020 gave the equivalent shade as 5 dips in Feb, 2021

The dark blue that was achieved from 12 dips in May, 2020 was not achieved, even after 24 dips in Feb 2021

The subtle differences in the darkest shades are hard to discern from the photos – but they are there.

I now realize the value of having a number of vats: from quondam to new, weak to potent. Information technology's something I have heard Michel Garcia say on more than than one occasion, simply sometimes we simply have to observe and larn the lessons on our own.

This spring, I will not discard my weakening vats, but will add another vat for the potent, deep blues that I am currently needing to build up blackness colors on my woven cellulose fabrics.

I have used one-bathroom acid dyes extensively in my own work, especially for cross-dyeing my handwoven fabrics that are constructed of both cotton and wool. The acid dyes attach only to the wool or other poly peptide cobweb. When combined with indigo, which attaches to both cellulose and protein fibers, very interesting combinations can be achieved.

-

Cross dyeing on wool and cotton wool using indigo and madder root -

Cantankerous dyeing on wool and cotton fiber using indigo and alkanet root -

One bath acid dye with henna leaf powder

The "one-bath acrid dyes" that Joy Boutrup and I discuss in The Art and Scientific discipline of Natural Dyes include henna, madder, pomegranate, cochineal, lac, and rhubarb root. Since publishing the book, I have extended the palette with the addition of other dyes, mostly due to the help from Michel Garcia when he was here in my studio several years ago.

Michel and I were discussing dyes that I might choose Not to use considering of their poor tolerance to light. Alkanet is i of those. A purple color is extracted from alkanet root by ways of an alcohol extraction. The color is beautiful and enticing , only very fugitive. Michel indicated that the alcohol extraction does some impairment to the dyestuff.

The one-bath process extracts different dyes from the plant than from those that are obtained from using more than traditional methods. While experimenting, we treated alkanet as a i bathroom acrid dye (for protein fiber merely) and a beautiful purplish chocolate-brown colour emerged that is quite fast to light. It'due south a warm neutral color that I accept not achieved using any other dye.

-

Alkanet on wool with alcohol extraction and alum mordant -

Alkanet using i bath acid dye on wool – no mordant

Safflower petals are another dye source that he showed me can be used equally a one-bath acrid dye. A gilt xanthous is dyed onto wool or silk that is quite lightfast and requires no mordant. The safflower petals can still be used after the i-bath procedure to extract the traditional reds and pinks by altering the pH, though the red colors are still not fast to light.

-

Yellow extracted from safflower petals using 1 bath acrid process (on silk) -

Safflower pink on silk

These discoveries energized my own piece of work and as I went deeper, I began noticing that many of the found dyes that are used for the ane-bath acid procedure have also been used as natural pilus dyes: henna, madder, alkanet, dock, rhubarb root, cassia leaves (Cassia obovata, also referred to as "neutral" or "colorless" henna). These can all exist used successfully for 1-bath acid dyes and event in very lightfast colors. Dried Indigofera tinctoria leaves ("black henna") are also used equally a dye for hair and when combined with henna results in a very night color.

The application of henna as both a hair dye and as mehndi, (a temporary dye for the skin) is the same: finely ground plant textile is mixed into a paste with water, acidified with lemon juice, and allowed to sit on the hair or skin for several hours. When the paste is washed away the color remains. These are considered non-permanent dyes for the peel and pilus and may be repeated after the color fades.

Acid dyes are very lightfast merely are not as fast to washing. (This applies to both natural acrid dyes and synthetic dyes.) If practical to the skin or hair, they will eventually exist washed away. BUT importantly, nosotros don't wash our woolen fabrics as aggressively or every bit often, thus the dyes are suitable for wool or silk textiles.

I was curious to encounter if these dyes could be used for direct application to woolen fabrics. There is a Moroccan tradition of using finely ground henna leaf in this fashion on fabrics woven of wool and cotton. It is well documented in the book Dice Farbe Henna / The Color of Henna Colour of Henna: Painted Textiles from Southern Kingdom of morocco by Annette Korolnik-Andersch and Marcel Korolnik.

-

Henna, alkanet and madder practical to wool /cotton material

I made a paste of each of these dyes using finely ground found material with a minor amount of water. I acidified the paste with vinegar (citric acid would damage fabrics that contained cotton) and allowed it to sit overnight one time applied to the fabric. The colors are stiff and articulate, although some dyes spread more than than others. They are not quite every bit deep as those dyed in a heated bath, though steaming the textiles will result in deeper colors.

I have observed that the freshness and quality of the dyes matter. Organic henna, used for hair and peel dye, resulted in a vivid clear color while other henna powders that I accept used produced duller colors.

-

Madder root (Rubia cordifolia) -

Henna foliage (Lawsonia inermis) -

Rhubarb root ( Rheum officinale) -

Safflower petals (Carthamum tinctorius) The yellow dye spread, while the pinkish dye, released from the acrid paste, attached just to the cotton. -

Henna leaf, with a secondary application of indigo leaf pulverization in the heart -

Dock root (Rumex crispus) -

Cassia leafage (Cassia obovata ) -

Indigo leaf (indigofera tinctoria)

This approach has revealed to me one more fashion of understanding and using natural colour and given me more opportunity to combining information technology with my own woven textiles. Information technology has taught me more almost plant categories, alternative applications, and the need to constantly be open to new ideas.

I now have, and am actively using, three 50 liter (15 gallon) indigo vats, in addition to a 100 liter (thirty gallon) henna vat.

I am loving the size of the 50 liter vat! The vessel is tall and narrow. Information technology's but the correct shape for a vat, with a relatively reduced surface area, and a great size for studio immersion dyeing. I have been dyeing samples, skeins of yarn, my ain shibori work, and even wear in those vats.

Like most dyers, I began with what I then idea was a "large" five gallon vat. That is still the nearly practical size for instruction workshops and I am guessing that it'due south the size/shape that many dyers start with – and most stay with.

But, I don't remember it's the best for studio work. IT'S TOO Modest! When working with natural indigo vats, whether they are fermentation vats or quick reduction vats, there is going to be a lot of 'sludge" at the bottom of the vat. With some vats this can be upward to 1/three, or more, of the full depth. If you proceed the textiles higher up that sludge , it doesn't exit much room for dyeing. I am afraid that many dyers might tend to let their textiles dip into that "wasteland" at the lesser, exposing the fibers to concentrated lime or plant textile. Equally a consequence, the dyeing is not as good equally it could be.

A 50 liter/fifteen gallon liter vat is a much greater commitment than an 18 liter/ v gallon saucepan, both in terms of financial investment and engagement. Withal, information technology is so much more useful and the dyeing is and so much meliorate! It's also harder to simply "give up" on a larger vat. Yous get better at maintaining and problem solving.

This is the vessel that I utilise. It's a hard, durable plastic. I identify information technology on a wheeled dolly. Otherwise it'due south also hard to motility. A heavy duty constitute caddy works simply fine.

Sometimes I suspend samples and other pocket-size pieces from the top, using stainless hooks and wooden rods.

I accept experimented with several types of baskets, nets, etc. to hold my larger textiles and keep them away from the lesser of the vat. I take finally settled on using a large, mesh laundry handbag. It fits the vessel nicely, is flexible, re-usable, completely contains the textiles, and prevents things from getting lost in the bottom.

Every bit I experiment with the fermentation vats, it becomes necessary to do a lot of dyeing. I am working on a long-term woven serial, merely regular dyeing has get increasingly important with my fermentation vats – and more possible, now that I am staying home.

I've taken some of my white or light colored article of clothing (too impractical to wear in the studio) and turned them into indigo dyed "dyeing clothes". It took some courage to put a big linen tunic in the vat just I've been surprised at the even dyeing of even these larger, synthetic pieces. I e'er exercise at least 3 long dips into the vat, which will assure that the dye "evens out". I would never accept attempted dyeing habiliment in a 5 gallon vat.

Maintaining a good dyeing temperature is important, specially with the fermented vats. I take successfully used a band-type pail warmer and plugged it into a digital temperature controller. This has been keeping the vats at a regular temperature in my unheated studio.

AND if you are going to make wood ash lye for a fermentation vat, this is the time of year to connect with friends who are called-for wood. You lot will want to identify someone who burns only hard woods in an efficient wood stove. That will result in the best ash for making lye.

Dominique Cardon, French researcher of natural dyes and author of the classic reference book, Natural Dyes: Sources Tradition, Engineering and Science, has simply provided dyers some other important resource and insight into the natural dye procedure: Workbook, Antoine Janot's Colours

For several years, Cardon has been translating and publishing a series of books that certificate the work of 18th century French dyers. The 18th century was the classical menstruum of wool dyeing in French republic. Last yr, Des Couleurs cascade les Lumières. Antoine Janot, Teinturier Occitan 1700-1778 was released, but only in French. This book was based on the original dye notebooks of Antoine Janot, a professional dyer from the Occitan region of the country.

Workbook, Antoine Janot'south Colours, which Dominique wrote in collaboration with her daughter Iris Brémaud, begins by providing background information on Janot and a description of the project. The most useful part of this small book to dyers is its practical nature. It includes a total palette of Janot'southward colors and their recipes forth with procedure information. It is written in both French and English.

The dyed colors are represented as visuals that were matched from actual wool samples from the original notebooks. Cardon used a color analyzer and the CIELAB organization to accurately portray each hue. CIELAB is an international organisation that scientifically analyzes colors by using a arrangement of coordinates to "map" them graphically and very precisely.

Descriptions of mordanting and dyeing include % weight of dye materials along with other additions that were made to the baths. In some cases, helpfully, an explanation of the WHY is included.

The cardinal to some of the color palette is a full gradation of indigo dejection, from the very palest to very deep. Each blue has its own proper noun such as "crow's wing" (the very darkest) to "off-white blue" (the very palest). The CIELAB organization allows an accurate visual description of each of these dejection.

These blue shades are critical to achieving greens, purples and greys. Instructions for mixed colors designate which blue to kickoff with. A total range of indigo dejection, from lightest to darkest, is not an easy matter to accomplish. I accept been working on that very thing consistently for the terminal months in my own studio, and so information technology is especially meaningful to me right now.

I have recently been doing color replication work for logwood purple using a combination of indigo and cochineal. A systematic approach to dyeing the initial indigo blues is a huge help in approaching this kind of color matching.

Information technology is rare to be able to gain such a deep insight into a professional dyer'southward process and results. Historical color descriptions, such every bit "vino soup", "celadon greenish", and "cherry-red" become more than just words on a folio when colors are able to be seen accurately with the eye.

For dyer's looking for a deeper insight into the world of professional person natural dye, this volume is a treasure.

I ordered my copy directly from French republic and information technology took several weeks to go far. Co-ordinate to Charlotte Kwon, the book volition also soon exist available from Maiwa.

On some days information technology's difficult to believe how recently we traveled freely worldwide, meeting new people and experiencing new places. Iii years ago I attended the natural dye symposium in Madagascar, where I offset met Hisako Sumi who started me on my current journey of making and maintaining indigo fermentation vats. As I was harvesting Persicaria tinctoria leaves in the garden, I was reminded of the fresh leaf indigo dyeing that we saw being done in Republic of madagascar.

-

Indigofera erecta -

-

colour begins very light -

-

color is deepened by time in the bath of fresh leaves -

Many of us are growing indigo in our gardens right now and accept likely had the pleasure of experimenting with fresh leaf indigo dyeing on silk. It's like magic to see the lovely turquoise color emerge from the cold leaf bath.

The indigo that grows in Madagascar is Indigofera erecta. Information technology is a perennial in that climate and the leaves are harvested from the bushes as needed. The leaves were used to dye the raffia fibers directly. There was no vat or reduction.

Notwithstanding, the dyers took this "cold" process one step further. The ambient temperature dyebath produced a lovely clear turquoise blue color on the raffia. When estrus was applied, the colour deepened and shifted.

This arroyo of oestrus application was new to me. When I inquired about it, both Hisako and Dominique Cardon indicated that they were both familiar with this phenomenon. Hisako sent me an paradigm from a scientific report washed by Dr. Kazuya Sasaki that documented the range of color that could exist obtained from fresh leaf woad past increasing the temperature. Once armed with that information I was able to reproduce that range of colour, nearly exactly, on silk and and on multi-fiber test strips, though the results were not precisely the same as those we saw in Madagascar.

I have always understood that the procedure of fresh leaf dyeing with indigo is primarily used on silk – a protein. Yet, the dyeing nosotros witnessed in Madagascar was done on raffia. Why did this process work and so well on raffia- a cellulose cobweb? I posed the question to my colleague, Joy Boutrup. "Raffia is about pure lignin" she said. Lignin is an organic polymer and has a strong analogousness for dye.

This calendar week I repeated the tests with Polygonum tinctorium on silk broadcloth and raffia. I used a greater quantity of leaves this fourth dimension – a blender total of leaves for a few pocket-sized samples vs. less than 100 chiliad. I puréed the leaves this time rather than chop them up. The "coldest" bluish is a deeper shade but otherwise the results are very like. I freely admit that I don't understand, chemically, why the colors change with the temperature:

- Are in that location other dyes attaching?

- Has the indigo been transformed past the temperature?

Maybe someone else can enlighten.

-

silk dyed with fresh leaf indigo 2017 -

silk and raffia dyed with fresh leaf indigo, 2020

I accept always suspected that the lightfastness of the fresh foliage indigo dye is not to the same level every bit the color obtained from a well reduced indigo vat. I will exercise lightfast tests on this range of color and report back in a later blog.

Three years ago, the trip to Republic of madagascar taught me nearly an arroyo to dyeing that I had never seen earlier – truly one of the gems of travel. We may not exist free to movement around for now, Simply other opportunities continue to present themselves on the web. One of the most heady upcoming events is this year's Textile Gild of America Symposium: Hidden Stories: Man Lives.

Originally planned to exist held in Boston this fall, Hidden Stories: Human Lives will now be alive and completely online October fifteen-17. This biennial effect brings together scholars, curators, and artists from all over the world who will present their original enquiry in the form of organized panels and talks. Fee structures for the symposium accept been completely re-vamped in gild to make this upshot accessible to all – no thing where in the globe you might exist. Registration has just opened and you tin see the full program here. In add-on, You can also read about the keynote and plenary speakers. Hope to come across yous at that place!

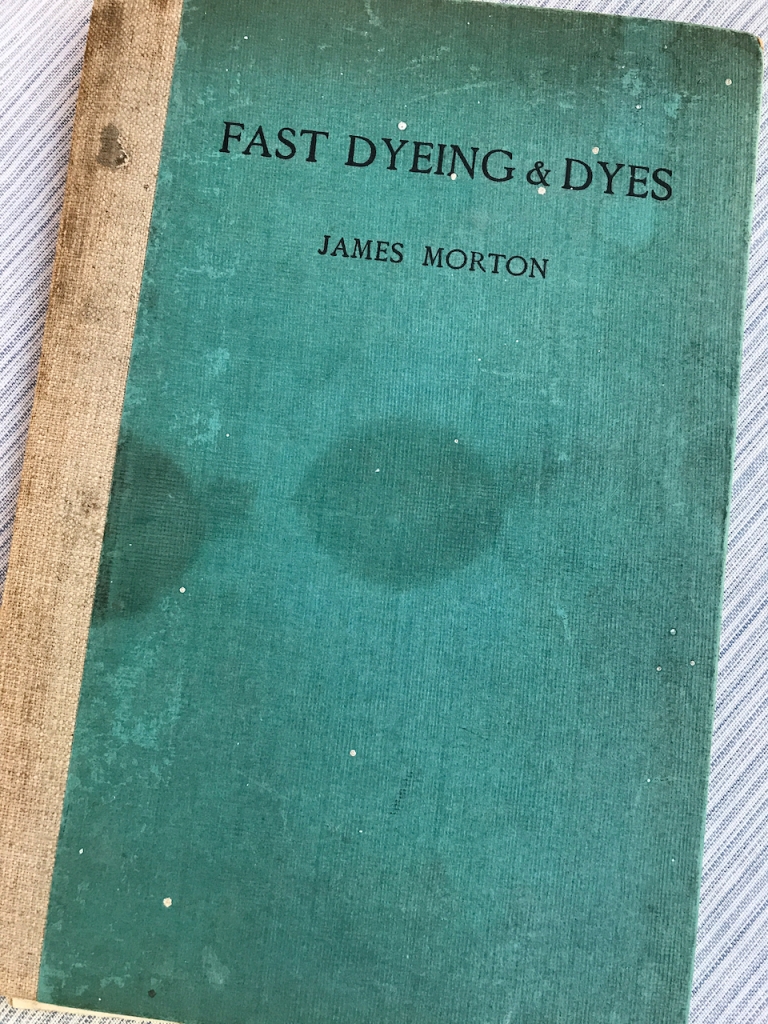

A dearest friend recently put a small booklet into my easily: Fast Dyeing and Dyes by James Morton. It is the spring proceedings of a lecture that Morton delivered to the Royal Society of Arts in London, 1929.

Morton'due south father, Alexander Morton, founded the weaving visitor of Alexander Morton & Co, in England in the late 19th century. The son, James was trained every bit a chemist and specialized in the use of permanent lightfast dyes for cellulose textiles. In the narrative, James recounts work that he achieved in 1903 to develop a palette of lightfast dyes for textiles. Information technology was an interesting fourth dimension in the development and employ of material dyes. Up until the second half of the 19th century, natural plant and insect dyes were the source of all textile colors, but by the early on 20th century chemical dyes were quickly replacing the natural dyes in industry.

Morton's company specialized in producing woven furnishing fabrics for curtains, carpets, upholstery and tapestries. He spoke of observing one of the company's tapestries in a shop window display. Afterward only a week's fourth dimension, the colors had faded dramatically. This led him to question the dyes they were using. He commandeered his family greenhouse (which had previously contained tomato plants) to set up upwards a series of lightfastness tests. He tested fabrics from his ain visitor as well as those from others. The results he described equally "staggering". Even deep shades of color applied to expensive fabrics became almost white after only a calendar week'due south time. He made detailed notes and documented each sample.

Afterwards making these careful observations, his goal became one of identifying a few colors (produced past chemistry) that could be relied upon and that performed well. Morton believed that even a limited range of colors that would remain on the fabric over time was far preferable to a large palette of color that would degrade apace. The company trademarkSoundour was born – a combination of the give-and-take "sun" and the Scottish word "dour" pregnant stubborn or hard to move. He identified the Alizarines every bit "good friends" which kept their shades. This was a course of chemic dye, based on the constructed manufacturing of alizarin, the primary carmine colorant in madder root. In 1869 it was the first natural dye to exist produced synthetically. Colors derived from minerals were adequate equally sources for low-cal browns. Indigo was deemed unsatisfactory for longevity on cellulose just Indanthrene vat dyes, new to the market, served every bit a good source of yellows, blues and greys. (These are the same vat dyes that I previously used in my own work.)

All the called chemic dyes were tested thoroughly, both in the greenhouse and on rooftops in India, where the sun was hot and intense and the humidity was high. The result was a carefully chosen palette of color that could be advertised as reliable and exist priced accordingly – significantly higher priced than other fabrics on the market. The goal was to have colors that would last as long as the textile itself.

What strikes me about this story is the recognition of lightfastness beingness of value at a time when at that place was such excitement about the power to easily produce most whatever color through the utilise of the new "chemical" dyes. Morton changed the industry's awareness of and arroyo to the use of constructed dye colour. Interestingly, he stated that "Some manufacturers questioned the wisdom of raising the standards and so high…"

I tin can't aid merely encounter a parallel to today's re-discovery and excitement almost natural colors. That excitement frequently causes a "bullheaded spot" when it comes to objectively looking at the longevity of some dyes. If the experience of making color is the singular goal and then it doesn't matter then much how long the color will ultimately terminal, merely if at that place is a customer with an expectation that the colour volition last as long equally the fabric, then colorfastness is a different and critical matter.

Professional natural dyers accept made decisions over the centuries to provide customers with the best quality colors possible. The Dyer's Handbook: Memoirs of an 18th -century Chief Colourist, by Dominique Cardon makes the following statement nearly testing for "false" colors: "Information technology is not enough for the dyer to have acquired knowledge on the drugs that are necessary to him and on their properties, and to have managed to apply them with success. He must too distinguish the fast colors from the simulated ones…"

All dyes fade – that's a fact. And all textiles will deteriorate. My colleague, Joy Boutrup, says that acceptable fading of a dye results in a lighter version of the original hue while the integrity of the original color is maintained: a lighter indigo blue, a softer madder ruddy etc. – not an "ugly beige color" that has no relationship to the original. And the ultimate goal is that the color final as long as the textile.

Source: https://blog.ellistextiles.com/

Postar um comentário for "The Art and Science of Natural Dyes Principles Experiments and Results"